Democratization has taken very different paths in the countries surveyed by the Pew Global Attitudes Project. Most Eastern European countries began their transition to democracy with the collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989. But 14 years later, many people still do not completely embrace many aspects of democracy, in part because they associate the transition with economic turmoil.

In Latin America and Asia, many countries have moved to freely elected governments only in the past 20 years. Democratization in Africa has taken hold even more slowly, hindered by authoritarian regimes, wars and enormous social problems. And it has yet to fully emerge in most of the Middle East.

What unites the people of these regions is that, for the most part, they highly value political rights and civil liberties. But there is a definite disconnect between their democratic aspirations and their perceptions of day-to-day reality. While people everywhere want honest elections, a fair judiciary and a free press, they often complain that their own country lacks these building blocks of democracy.

However, global attitudes on democracy and civil liberties are hardly uniform. Majorities in most countries say it is very important to live in a country that has honest multiparty elections. But there are several notable exceptions, including Russia, South Korea and Indonesia. And in general, people around the world value an impartial judiciary above honest elections or other aspects of democracy.3

In Eastern Europe, there is clear evidence that the political mindset formed during decades of communist rule has yet to completely dissipate. Significant percentages in Russia, Bulgaria and Ukraine, in particular, continue to disapprove of the political changes that have taken place since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Solid majorities in every Eastern European country surveyed, with the exception of the Czech Republic, believe a strong economy is more important than a good democracy. In other economically struggling regions such as Latin America and Africa, people are much more likely to view a good democracy as more important than a strong economy.

The analysis in this section proceeds through 35 democratizing countries in four regions – Eastern Europe, Latin America, Asia and Africa. The Middle East/Conflict Area is covered in the chapter entitled “Muslim Opinion on Government and Social Issues”. The Pew Global Attitudes Project pays particular attention to issues in Eastern Europe because of the dramatic changes there over the past 15 years, and the benchmark Pulse of Europe survey that Pew conducted in the region in 1991. To allow for trend comparisons, the German survey updates attitudes on democracy in former East Germany and former West Germany.

I: Eastern Europe

With the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union two years later, Eastern Europeans began a rocky transition from one-party rule and a command economy to democracy and a free market system. More than a decade later, support for this transformation remains uneven.

Barely half of those in Ukraine (50%), Bulgaria (49%), and Russia (47%) say they approve of the political changes in their country since the fall of communism. While modest, this represents significant growth in support for political change in Russia and Ukraine since 1991 when, as the Soviet Union was collapsing, only about a third in each country endorsed the move toward democratic rule. But in Bulgaria, the number endorsing these political changes has fallen significantly over the past 11 years (from 60% to 49%).

By contrast, solid majorities in the Czech Republic (83%), the Slovak Republic (69%) and Poland (62%) welcome the political changes of the post-communist era, as they have from the beginning. In 1991, majorities in the Czech Republic (74%) and Poland (64%) and half of those surveyed in the Slovak Republic (48%) said that they approved of the political changes that were then just underway.

To the extent that there is still dissatisfaction with changes since 1989, it is rooted in the economic hardship of the transition. The Pew Global Attitudes survey reveals that most Eastern Europeans say the gap between rich and poor in their country has gotten worse, not better, over the last five years. More than eight-in-ten in every country except Ukraine say inequality has grown in their country.

Economic concerns appear to be fueling political dissatisfaction. In every Eastern European country, those with high incomes are more likely than those with low incomes to approve of recent political changes. In Bulgaria, for example, less than a third (31%) of those with the lowest incomes approve of the recent political changes, compared with 83% of those in the high-income bracket.

Young Favor Changes More

Disapproval of political change in Eastern Europe is greater among older Eastern Europeans and those with less education. In Russia, about six-in-ten (59%) of those age 60 or older disapprove of the changes since 1991, compared with just a third (35%) of those aged 18 to 34. In Bulgaria, 62% of those age 60 and older disapprove of the changes since then, compared with 35% of those under age 35. This generation gap exists in every Eastern European country except the Czech Republic, where approval of recent political change is extraordinarily high among both old and young.

In addition, respondents with a primary school education or lower are much more likely to disapprove of political changes than those who have attended some college. This relationship is true in every country except Ukraine.

Civil Liberties Backed, Less So in Russia

Eastern Europeans embrace political rights and civil liberties, yet they generally place a lower value on such democratic ideals than do people in other nascent democracies or well-established Western democracies. Russians, in particular, give low priority to political rights and liberties. Overall, Russians are less likely than other Eastern Europeans to say that it is very important to live in a society that affords freedom of speech, honest multiparty elections, religious freedom, a free press, and a fair judiciary.

Half or more respondents in the Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Poland, the Slovak Republic, former East Germany and Ukraine say that it is very important to them that “honest elections are held regularly with a choice of at least two political parties.” Far fewer people in Russia take the same position (37%), although most Russians say it is at least somewhat important that they live in a country with honest multiparty elections (40% somewhat important).

When Eastern European attitudes are compared to the views of people in former West Germany, an East-West political-values gap emerges. Russians give lowest priority to democratic ideals, former West Germans the highest, with other Eastern Europeans in between.

More than eight-in-ten people in former West Germany (83%) say that honest multiparty elections are very important to them. In Eastern Europe, Slovaks and Czechs place the greatest emphasis on free elections. Aside from Russians, Poles and Bulgarians are least likely to say honest multiparty elections are important to them.

Impartial Judiciary Favored

Eastern Europeans place the greatest value on a fair judicial system. Solid majorities in every country in the region say that it is very important that they live in a society with a judicial system that treats everyone the same. This sentiment is particularly strong among Czechs (84%), former East Germans (84%), Bulgarians (79%) and Ukrainians (82%).

Even here, however, there is a modest gap between East and West. Former West Germans (87%) still place a higher value on a fair judiciary than do Russians, Poles, Bulgarians, Ukrainians or Slovaks. Only the Czechs and former East Germans share the former West Germans’ level of concern for honest judges.

But there is broad agreement across the region that the goal of an independent judiciary is not being achieved. Majorities in every eastern European country – with the notable exception of former East Germany – say the phrase “there is a judicial system that treats everyone in the same way” does not describe their country well. Just 5% in Bulgaria and the Czech and Slovak Republics say this describes their country very well.

Religious and Press Freedom Backed

Religious freedom is viewed as most important in Eastern European countries where the Catholic and Orthodox Churches have a strong presence: Poland (62% very important), the Slovak Republic (60%) and Ukraine (55%). In Russia, where atheism was official doctrine under communism, notably fewer respondents (35%) say religious freedom is very important to them.

The Global Attitudes survey also asks whether religion is a matter of personal faith that should be kept separate from government policy. In every country in Eastern Europe, regardless of their religious tradition, large majorities agree that religion is a purely private matter.

But Eastern Europeans differ over the importance of freedom of the press. A free press is as highly valued by Czechs (71% very important), Slovaks (66%) and Ukrainians (64%) as by former West Germans (65%). Solid majorities in each of these countries say it is very important that they live in a country where the media can report the news without government censorship. But that ideal wins far less support in Russia (31% very important), where the media is still struggling to freely report the news.

Throughout Eastern Europe, large majorities of the public say they value freedom of speech. But most do not place high value on it. Just three-in-ten Russians, about half of Bulgarians (48%), and majorities in Poland (55%), the Slovak Republic (58%) and Ukraine (59%) say it is very important that they live in a society where they can openly say what they think and can criticize the government. More people in the Czech Republic (65%) and in former East Germany (70%) claim that freedom of speech is very important, but significantly more West Germans hold that view (84%).

In Eastern Europe, and throughout the other regions surveyed, more highly educated people consistently place greater importance on freedom of speech, the press and religion, and honest elections than do those with less education. Higher income respondents are also most likely to value these rights, but the relationship is much less consistent. There is no consistent difference in attitudes across age groups.

Civilian Control Not a Priority

Civilian control of the military is a democratic principle that finds relatively little favor among Eastern Europeans – not even in Poland where the army seized control and declared martial law in 1981. In every country except former East Germany, fewer than four-in-ten say it is very important to them that they live in a society where the military reports to the civilian leadership. Just 29% in Poland, 21% in Bulgaria and 20% in Russia believe this principle is very important.

In part, such sentiment reflects widespread trust of the military. Majorities everywhere except Ukraine say the armed forces have a good influence on how things are going in their country. Only in Ukraine does a plurality (44%) believe that the military has a bad influence. Even there, however, fewer than four-in-ten (38%) give high priority to the principle of civilian control.

Eastern Europeans generally feel their countries fall short of meeting their expectations on democratic ideals. Whether it is freedom of speech, honest multiparty elections, press freedom or a fair judicial system, substantially fewer than half of those surveyed say these democratic ideals describe their countries very well.

Rather, majorities say these ideals somewhat or very well describe their countries. And less than half the public in Bulgaria (43%), Russia (42%) and Ukraine (45%) believes civilians are in control the military in their country. Between 20% and 40% in each country, on average, say these ideals do not describe their country well.

Progress In Last Decade

Nonetheless, when asked about the pace of progress in specific areas over the last decade, solid majorities say they now have more freedom to say what they think, to join any political organization they want, and to choose whom to vote for without feeling any pressure. Among the six countries surveyed on these issues – the Czech and Slovak Republics, Bulgaria, Poland, Ukraine and Russia – more than two-thirds in every country say that today they have more freedom to say what they think.

Similarly large percentages among all six publics say they have more freedom to join any political organization they choose. And with the exception of Russia, solid majorities say they have more freedom to decide whom to vote for, compared with 10 years ago. About half of Russians feel that way (51%), while 24% report no change and 18% say they have less latitude in deciding their vote than they did a decade ago.

But in another area – personal safety – Eastern Europeans agree that things have deteriorated over the past decade. No fewer than six-in-ten in all six countries yes – it is surveyed say there is less safety from crime and violence now than a decade ago.

Economic Concerns Drive Age Gap

Older people in Eastern Europe are more likely to disapprove of the changes in the last 10 years than are younger people. At the same time, when asked how well various political rights and civil liberties describe their country, older people are as positive or even more positive than the younger generation.

It is only when asked generally about post-communist political changes that older Eastern Europeans voice more concern than the younger generation. This concern has a strong economic component, as the region‘s political evolution has been accompanied by a dramatic shift to a free market economy. Older Eastern Europeans are less likely than younger people to think they are better off in a free market economy, and the older generation is more likely to be dissatisfied with their household income.

Bribery – Occasionally Necessary

Most Eastern Europeans say they seldom if ever need to give gifts, perform favors or pay bribes to government officials to secure services or documents the government is supposed to provide, but the practice does occur. Four-in-ten Ukrainians (41%) say that in the last year they have engaged in the practice, although relatively few say it happens frequently (4% very often/11% somewhat often).

A third of Russians say they have had to bribe government officials in the past year, as have 27% in the Slovak Republic, 24% in Poland and 20% in Bulgaria. Bribery is reported least often in the Czech Republic – fewer than one-in-ten (9%) say they have had to bribe a government official to get services or documents.

Young people are more likely than older respondents to say they have paid bribes. For example, in Ukraine, nearly half of those ages 18 to 34 (47%) say they have offered a bribe in the past year, compared with a quarter (27%) of those ages 60 or older. A similar difference between the old and the young exists in Bulgaria, Poland, Russia and the Slovak Republic. In Russia, people with some college education were also more likely to report offering a bribe, and in Bulgaria, Russia and the Ukraine, the wealthy were more likely than those in lower-income brackets to report they have had to pay a bribe to a government official.

Strong Economy Trumps Good Democracy

With the exception of the Czech Republic, at least six-in-ten respondents in every Eastern European country say they believe a strong economy is more important than a good democracy. Overwhelming majorities in Russia (81%), Ukraine (81%) and Bulgaria (74%) opt for a strong economy. Only in the Czech Republic does a majority (59%) choose democracy over economic growth. But even there, four-in-ten (38%) people prefer a strong economy to a good democracy.

Public opinion on this question is linked to people‘s own financial situations. In four Eastern European countries – Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Russia and the Slovak Republic – higher income respondents are more likely to favor a good democracy over a strong economy. In the Slovak Republic, for example, almost half (49%) of those in the highest income bracket choose a good democracy compared with three-in-ten (30%) of those in the lowest income bracket.

Education also is a factor in these attitudes. In the Czech Republic, three-quarters of those with at least some college (75%) prefer a good democracy compared to just over half (55%) of those with a primary school education or less. In the Slovak Republic, younger people are more likely to choose a good democracy over a strong economy. Half of those ages 18 to 34 (50%) choose a good democracy compared to a third (32%) of those ages 60 and older.

Prosperity Very Important

Consistent with these attitudes, overwhelming majorities in nearly every Eastern European country rate economic prosperity as a very important objective. The only exception is former East Germany, where a slim majority says economic prosperity is very important. In three nations – Russia, Ukraine and Bulgaria – more people cite prosperity as a top goal than say that about any aspect of democracy.

This desire for national economic success contrasts with reality. Majorities throughout the region – except in former East Germany and the Czech Republic – say their countries are not prosperous. Fully 83% in Bulgaria say their country is not enjoying prosperity – one of the highest percentages of any country surveyed. Nearly as many Slovaks and Poles hold that view as well (76%, 74%). By comparison, people in former East Germany and the Czech Republic are much more upbeat about economic conditions. Roughly two-thirds (68%) of those in former East Germany say economic prosperity describes their country well, and 55% of Czechs agree.

Many Prefer Strong Leader

Many Eastern Europeans also say that to solve their countries‘ problems they prefer a strong leader rather than a democratic form of government. Solid majorities in Russia (70%) and Ukraine (67%) opt for a strong hand in government leadership. This is a reversal of 1991 sentiment when most people in Russia (51%) and Ukraine (57%) favored a democratic government to solve problems.

In Poland and Bulgaria, opinion is divided on this issue, with as many people favoring a strong leader as a democratic form of government. The Czech and Slovak Republics stand out with overwhelming majorities favoring a democratic form of government (91%, 86%).

In every country in the region, those in the highest income bracket are more likely to choose a democratic form of government over a strong leader than those in lower income brackets. For example, in Bulgaria more than seven-in-ten (72%) of the rich chose a democratic form of government, compared with a quarter of the poor. Conversely, people with lower incomes favor a strong leader. In Poland, 59% of those with low incomes choose a strong leader to solve national problems, compared with 23% of those with high incomes.

II: Latin America

Until recently, free and fair elections have had an inconsistent history in Latin America. Most of the countries in the region have only achieved elected civilian rule within the last two decades.

Despite that history, majorities in six of the eight Latin American countries surveyed favor a democratic government over a strong leader to solve their nation‘s problems. In Mexico and Venezuela, democratic government is favored by better than three-to-one. Only in Honduras and Brazil do majorities dissent from this view.

In contrast with most countries in Eastern Europe, recent economic hardships have not led Latin Americans to favor a strong economy over a good democracy. Majorities in economically devastated Argentina, as well as in Venezuela, Peru, Guatemala and Mexico, say they prefer democratic freedoms to a strong economy.

This preference for democracy is particularly significant given the widespread economic pessimism in the region. Solid majorities in every Latin American country surveyed consider economic prosperity as a very important objective, but there is little sense that the goal is being fulfilled. In Argentina, fully 86% say the country is not experiencing prosperity – among the highest percentages of all countries surveyed.

Most Say Military Not Under Civilian Control

Despite the steps taken toward democracy in several Latin American countries, there is a widespread perception that the military is not under the control of civilian leaders. Almost six-in-ten in Brazil (58%), Venezuela (58%) and Guatemala (57%) say civilian control of the military does not describe their country well.4 Only in Mexico is there a clear perception that the military is under civilian control; even so, just 30% of Mexicans say it describes the situation in their country very well.

Most Latin Americans, however, do not regard civilian control of the military as a very important priority. Guatemala, which has a long history of military dominance, is the only country in which even a narrow majority (52%) says it is very important to live in a country where the military is under the control of civilian leaders.

Public support for other freedoms is more extensive. Solid majorities in nearly every Latin American country say that it is very important to them that honest elections are held regularly with a choice of at least two political candidates. The only exception is Bolivia, where 49% give multiparty elections high priority.

But far fewer say their country has honest multiparty elections. No more than four-in-ten in any country say it describes their country very well. People in Argentina take an especially negative view of their country‘s elections. Just a quarter of Argentines give their elections a passing grade, and only 9% give the nation high marks for honest elections. (This survey was conducted before the May 2003 presidential election in Argentina, and the October 2002 presidential election in Brazil).

Overall, Argentines are much more negative about their country‘s success in ensuring political rights and civil liberties than are other Latin Americans. These attitudes are associated with negative views of the government. Argentines who think the government has a bad influence on the way things are going are generally more likely to say that Argentina does not ensure people’s rights and liberties.

Differing Views of Political Changes

As in Eastern Europe, opinion on recent political changes in Latin America varies widely from country to country, reflecting different experiences with democracy. In Mexico, for example, the election of President Vincente Fox in 2000 was judged by many international observers as perhaps the first fair presidential election in Mexico‘s history. This milestone helps explain why a solid majority of Mexicans (62%) say they approve of the political changes that have taken place in the last five years.

Fewer respondents in Venezuela (47%) and Peru (40%) have such positive views. In Peru, the political landscape improved with the presidential election of Alejandro Toledo in 2001. But the government evidently has yet to regain public confidence after the chaotic departure of Alberto Fujimori, the autocratic former president. Since Victor Hugo Chavez was elected president in Venezuela in 1998, the political situation has spiraled downward, with an attempted coup and national strikes that have caused major economic disruption and significant opposition to many of the political and economic changes implemented by Chavez.

In Mexico, Venezuela and Peru, approval of recent political changes is tied to opinion about the president and the government. Those who say that the president has a good influence on how things are going in the country are more likely to approve of the political changes over the last five years than those who think the president has a bad influence. Similarly, those who approve of the government‘s influence also support how things are going politically in the country. (Approval of political change was asked only in Mexico, Peru and Venezuela.)

Low Confidence in Judiciary

As is the case globally, Latin Americans place high importance on a judicial system that treats everyone the same. Solid majorities in all eight Latin American countries surveyed say it is very important that they live in a country that has a fair judicial system. But people in several of these countries – especially Argentina and Brazil – have highly negative opinions of their current judicial systems.

More than eight-in-ten Argentines (85%) say that the statement “there is a judicial system that treats everyone in the same way” does not describe their country well; fully two-thirds say it does not characterize the country “at all” – by far the most negative rating in the world. Just one-in-twenty (5%) Argentines say an impartial judicial system describes their country very well.

Brazilians also judge their country‘s judicial system quite critically. Seven-in-ten (72%) think it is not fair and nearly half (47%) say an impartial system does not at all describe their country‘s judiciary. This view is shared, to a lesser extent, elsewhere in the region. Honduras is the only nation in the region where a majority of respondents (60%) say the judicial system treats everyone at least somewhat fairly, although a sizable minority (39%) disagrees.

Other Freedoms Valued

The ability to practice one‘s religion, freedom of speech and a free press also win broad support in Latin America. Freedom of religion is seen as especially important. More than seven-in-ten in every country except Bolivia say it is very important to live in a country where you can freely practice your religion. Just half of Bolivians agree, and support for other freedoms is also weaker in Bolivia than in other countries in the region.

Large majorities in every Latin American nation surveyed say that religion is a personal matter and should be kept separate from government policy. And, for the most part, people in these predominantly Catholic countries feel they are able to practice their religion without interference. In Mexico and Honduras, six-in-ten (61% in each) say that religious freedom describes conditions in their country very well.

Latin Americans take a less favorable view of the extent to which freedom of the press and freedom of speech are permitted. While majorities in every Latin American country surveyed say the media can report the news without government censorship to some extent, well under half in each say that statement describes their country “very well”. More than a third in Argentina (38%), Peru (37%), Guatemala, (36%), Venezuela (34%) and Brazil (34%) say that statement does not accurately reflect conditions in their countries.

Sizable minorities in several countries say the phrase “you can openly say what you think and can criticize the government” does not accurately describe their country. Nearly half of Guatemalans (48%) say that statement does not reflect conditions in their country, and more than a third of Peruvians (38%), Brazilians (35%), Argentines (34%) and Bolivians (34%) agree.

Reports of Bribery Vary Greatly

The extent to which Latin Americans say they have had to bribe government officials in the past year varies greatly from country to country. Argentines are the least likely to report paying bribes. Just 6% say the practice has occurred at least somewhat often in the past year, while 89% say they have not had a reason to pay a bribe or do a favor to obtain government services or documents.

In Venezuela, by contrast, 36% report that they have had to pay a bribe at least somewhat often in the past year. Fewer respondents in other countries say they have had to pay bribes in the past year. Roughly a quarter of those surveyed in Peru (24%), Mexico (24%) and Bolivia (23%) say they have had to pay a bribe or do a favor at least somewhat often in the past year to obtain government services or documents.

III: Asia

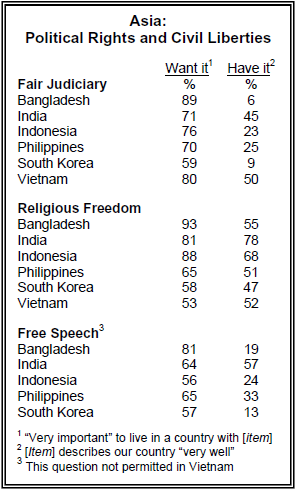

Asian respondents surveyed by the Pew Global Attitudes Project generally attach great importance to religious freedom and an impartial judiciary. But other aspects of democracy are less broadly supported – notably honest elections and freedom of the press.

Large majorities in the Philippines (77%), Bangladesh (71%) and India (64%) say that it is very important to live in a country that has honest multiparty elections. But only about four-in-ten in Indonesia (40%) and South Korea (43%) concur. Those are among the lowest marks of the 35 countries surveyed on democracy and civil liberties. (This survey was conducted before South Korea‘s presidential election in December 2002).5

For the most part, Asians do not express a high degree of confidence in their countries‘ elections. No more than four-in-ten in any country say that honest, multiparty elections characterize their country very well. Indonesians are the most negative in this regard – just 10% say it describes their country very well, and half say their country is lacking in this regard. Respondents in Bangladesh, in particular, place much greater value on free and fair elections than they believe their country delivers. (Questions on elections were not permitted in Vietnam; none of the questions on democracy were permitted in China).

Press Freedom Not Widely Valued

Freedom of the press is also not widely valued by people in the six Asian nations where this question was asked. (It was not permitted in Vietnam). Only in Bangladesh does a majority (64%) say that it is very important that the media can report the news without censorship in their country. In other countries, less than half the public agrees.

Most people give their countries, at best, middling ratings for press freedom. Only in India do as many as a third (32%) think the statement, “the media can report the news without government censorship”, describes their country very well. In South Korea, which recently enacted a criminal libel law allowing the government to jail journalists who express criticism, just 7% hold that view.6 More than four-in-ten in South Korea (43%) also say that a free, uncensored media does not describe the country accurately. Nearly a third in Bangladesh (31%) agree. In Bangladesh, violence and intimidation of journalists who are critical of the government has increased over the last few years.

Attitudes on the importance of civilian control of the military also vary widely in Asia. Fully six-in-ten Vietnamese rate this as very important, by far the highest percentage in the region. But only about one-in-five respondents in Indonesia (22%) and South Korea (18%) attach great importance to this ideal. Fully a third in Indonesia and nearly as many in South Korea (27%) and the Philippines (24%) say civilian control of the military is not too important or not important at all.

Religious Freedom, Fair Judiciary Very Important

Majorities in every Asian country surveyed say that religious freedom is very important to them. There is overwhelming support for religious freedom in predominantly Muslim Bangladesh (93%) and Indonesia (88%) as well as in religiously diverse India (81%).

There is general agreement among Asian respondents that they are able to freely practice their religion. As many as eight-in-ten in India (78%) give the country high marks for being able to practice their religion freely; 68% in Indonesia agree. This perception is not shared as widely in other countries; still, about half of respondents across Asia say religious freedom describes their country very well.

Like respondents in other regions, Asians also place a high value on an impartial judiciary. Solid majorities in every country in the region say this is very important, ranging from a high of 89% in Bangladesh to a low of 59% in South Korea. But at most, only about half – in Vietnam (50%) and India (45%) – think their country is doing very well in this regard.

People are particularly critical in South Korea and Bangladesh, where the U.S. State Department says the judicial systems are corrupt, slow and reluctant to challenge government decisions.7 Just 6% of Bangladeshis say an impartial judiciary describes their country very well, while 72% say it does not accurately describe conditions in their country. Only one-in-ten South Koreans (9%) give the judicial system high marks, while half say a fair judiciary does not characterize the current system.

The same pattern is apparent in Asian attitudes toward freedom of speech. Majorities in every country view the freedom to criticize the government as very important, but Indians are the only group in which most (57%) think the country is doing “very well” in ensuring freedom of speech. Again, the Bangladeshi public stands out with eight-in-ten (81%) saying that freedom of speech is very important but just two-in-ten (19%) saying it describes their country very well.

South Koreans, Indonesians Choose ‘Strong Economy’

On several measures, South Koreans and Indonesians stand out for the relatively low importance they give to democracy. When asked to choose between a strong economy and a good democracy, Indonesians overwhelmingly opt for a strong economy (69%-30%), while South Koreans are divided (49% strong economy/47% good democracy). In the other countries surveyed, solid majorities favor a good democracy over a strong economy.

In South Korea at least, this opinion may reflect frustration with the country‘s recent political history rather than a reaction to economic hard times. Most South Koreans (55%) view economic prosperity as very important, but that is far less than the number who hold that view in Indonesia (92%), Vietnam (84%), Bangladesh (82%) or the Philippines (75%). For the most part, the South Korean public believes that their country is economically prosperous (65%).

But South Koreans also disapprove of the political changes that have taken place over the last five years, a period marked by corruption scandals, economic problems and rising tensions with North Korea. Fewer than four-in-ten South Koreans (37%) approve of recent political changes, while a majority (56%) disapproves. (South Korea was the only Asian country where this question was asked).

But Not ‘Strong Leader’

Nonetheless, solid majorities in South Korea (61%) and four other Asian nations favor a democratic government, rather than a strong leader, to solve national problems. This opinion is broadly shared in Bangladesh (70%), Indonesia (65%) and to a lesser extent in India (54%). (This question was not permitted in Vietnam).

The exception is the Philippines, which became a symbol of democratic revolution in the mid-1980s when Ferdinand Marcos was overthrown and Corazon Aquino was elected president. Most people in the Philippines (55%) believe it is better to rely on a strong leader to solve national problems, while 41% favor a democratic government. As a point of comparison, only in Russia and the Ukraine is there greater support for a strong leader than in the Philippines (70% Russia, 67% Ukraine).

Bribery a Reality in Bangladesh

Most Asians report they have seldom if ever found it necessary in the past year to pay bribes to government officials. But Bangladesh is a notable exception – fully 44% of respondents there say they have had to engage in the practice very (20%) or somewhat often (24%).

Solid majorities in every other country say they either never have to bribe government officials or say it occurs “not at all” often. In every country, those who have attended college are more likely to have felt it necessary to offer a bribe than those with less education.

IV: Africa

By virtually any standard, support for democracy in Africa is broad and deep. Africans generally dismiss the idea that a leader with a strong hand is needed to solve their country‘s problems. Solid majorities in all African countries, with the exceptions of Mali and South Africa, believe their nations should rely on a democratic government, not a strong leader, to solve problems. This is particularly the case in Senegal (90%), Ivory Coast (84%), Kenya (77%) and Tanzania (70%).

Moreover, Africans overwhelmingly reject the idea that democracy is a “Western” form of government that would not succeed in their countries. By margins of at least three-to-one, people in all seven nations in which the question was asked instead agree with the statement: “Democracy is not just for the West and can work well here.” (This question was asked in selected countries in Africa, the Middle East and Asia).

In spite of the continent‘s grinding poverty, half or more in six of the ten African countries surveyed say they favor a good democracy over a strong economy. This view is particularly prevalent in the Ivory Coast (77% good democracy), Nigeria (63%) and Ghana (60%).

This survey was conducted prior to presidential elections in Kenya, in December 2002, and in Nigeria, in April 2003. Also, it was conducted before the outbreak of civil war in the Ivory Coast.

Elections Viewed Negatively in Kenya, Nigeria

Majorities in every African country say it is very important to live in a country with fair multiparty elections. Roughly nine-in-ten respondents in Senegal (87%) hold this view, and nearly as many in Kenya (85%), the Ivory Coast (84%), Mali (82%) and Uganda (79%) agree. In every country except Kenya and Nigeria, majorities say that honest, multiparty elections describe their countries at least somewhat well, although far fewer take a very positive view of the elections.

But Kenyans and Nigerians are negative about their countries‘ elections. In Kenya, a 58% majority feels that free elections do not describe conditions in their country. That was before the presidential election in December, which was judged free and fair by European Union observers. Similarly, about half of Nigerians (52%) expressed a negative view of their country‘s elections, prior to the recent round of presidential balloting.

Despite the criticisms of elections, people in Kenya and Nigeria are upbeat about the recent political changes in those countries. Seven-in-ten people in Kenya and nearly eight-in-ten in Nigeria (78%) say they approve of the political changes that have taken place in their countries over the last five years. Among all of the nations surveyed, only in Uzbekistan (85%) and the Czech Republic (83%) is there as much support for recent political changes.

Most Feel They Have Religious Freedom

As is the case with people in other regions, Africans view religious freedom and an impartial judiciary as highly important. Large majorities in every African country surveyed, with the exception of Angola, say it is very important that they live in a society that permits freedom of religion. This strong support for religious freedom prevails in both largely Muslim countries – Mali, Senegal and Nigeria – and largely non-Muslim countries – South Africa and Kenya.

There is broad agreement among Africans that they currently have religious freedom. This is especially the case in Senegal (89%), the Ivory Coast (80%) and Mali (77%), nations that also placed the highest importance on religious liberty. Nigeria, which has a long history of religious violence, is the only country in which a significant minority (25%) says that religious freedom does not describe the country well. Muslims in Nigeria (30%) are slightly more likely than Christians (22%) to perceive a lack of religious freedom. But even in Nigeria, 74% give the country a positive rating for religious freedom.

In nearly every African country, about seven-in-ten respondents view an impartial judiciary as very important; the only exception is Angola, where only half (51%) of the public says this is very important. But relatively few Africans say that an impartial judiciary describes their countries very well.

Solid majorities in three African countries – Kenya (64%), Mali (62%) and Nigeria (59%) – give their countries‘ judicial systems negative ratings. In Nigeria, majorities of both Christians and Muslims say an impartial judiciary does not describe the country well. Substantial minorities in other African countries – at least three-in-ten – also feel they lack a fair judiciary.

Free Speech: Ideal vs. Reality

Like other civil liberties, freedom of speech is broadly supported in Africa. Majorities in every country view the freedom to openly criticize the government as very important. But perceptions of whether this freedom exists vary widely from country to country.

Fewer than one-in-ten Kenyans (8%) say that free speech describes Kenya very well, while two-thirds (66%) give the country a negative rating. Fewer than three-in-ten Nigerians (27%) believe their country performs very well in this area, while 44% say freedom of speech does not describe their country. At the other extreme, most of those in the Ivory Coast (55%) feel the country has freedom of speech, but that was prior to the outbreak of violence last year.

Freedom of the press also is highly valued in Africa. Majorities in nine of ten nations surveyed – all except Tanzania – say that living in a country with a free press is very important to them. Again, there is a gap between its perceived importance and whether the media is currently permitted to report the news free of censorship.

Most Africans feel their countries‘ media can operate freely to some extent, although relatively few give their countries very high ratings for press freedom. Kenyans and Tanzanians are the most negative in this regard. Just 14% in Kenya give their country high marks for press freedom, though nearly half (48%) believe the statement “the media can report the news without government censorship” describes their country at least somewhat well.

In Tanzania, 22% say press freedom characterizes their country very well and 37% have a negative view of their country on this issue.

Majorities in seven of ten African countries surveyed say it is very important that the military be under the control of civilian leaders. Angola is a notable exception – 51% in that country say civilian control is not important.

But in every nation except Senegal and the Ivory Coast, substantially less than half the public says that civilian control of the military describes conditions in their country very well. Majorities in Uganda (58%) and Angola (56%), which have been devastated by civil wars, say the military forces in their countries are not under civilian control.

Corruption Widespread

More than in any other region of the world, official corruption is seen as widespread in many African countries. Fully 68% of respondents in Nigeria and 65% in Kenya say they have had to do a favor, give a gift or pay a bribe to a government official in the past year to get a service or document the government is supposed to provide. In Nigeria, 56% report this has occurred at least somewhat often, while 40% say that in Kenya.

Half of those in Angola (52%) and more than four-in-ten in Mali (44%), Tanzania (42%) and Uganda (40%) say they have had to offer a bribe to a government official at some point in the past year. Bribery is much less common in South Africa and Senegal; three-quarters of South Africans (76%) say they have not had to pay a bribe in the past year, as do 70% of Senegalese.