A continuing source of resentment toward the U.S. is the view that America pays little if any attention to the interests of other countries in making international policy decisions. Americans, as might be expected, do not subscribe to this view. Two-thirds of the U.S. public says the United States pays either a great deal (28%) or a fair amount (39%) of attention to the interests of other nations.

Majorities in only three other countries now share that opinion; India, where 63% say the U.S. pays a great deal or a fair amount of attention to their country’s interests, Indonesia (59%), and China (53%). In line with the general upsurge of positive feelings toward the U.S. in both India and Indonesia, these percentages are up sharply from past Pew Global Attitudes surveys.

In addition, increasing numbers in Pakistan and Lebanon say the U.S. pays at least some attention to their countries’ interests. About four-in-ten Pakistanis (39%) express that view, compared with 18% in 2004. There has been a comparable increase in Lebanon, though a majority of Lebanese still feel that the U.S. pays little or no attention to their interests. (However, among Lebanese Christians a solid majority (59%) feels that the U.S. is attentive to their country’s concerns.) And, fewer than one-in-five in Jordan (17%) and Turkey (14%) think that the U.S. takes their interests into consideration in its international policymaking.

Perceptions of U.S. unilateralism remain widespread among the publics of America’s traditional allies. In Germany, only 38% of respondents think the U.S. takes their country’s interests into account, the highest percentage in Europe. In Canada, just 19% feel the U.S. takes Canadian interests into account to any substantial degree when making policy. While these views have remained fairly stable in France, Spain and Russia over the last few years, the numbers of those viewing the U.S. as self-centered in its foreign policymaking have risen substantially in Canada, Great Britain and Germany.

Dealing with the U.S.

Publics in predominantly Muslim countries are split as to whether their governments follow the U.S. policy lead too closely. Pluralities in Pakistan (45%) and Turkey (36%) fault their government for hewing too closely to U.S. policies.

But in Jordan 58% of the public says that their government either deals with the U.S. just about right (43%) or does not go along with the U.S. enough (15%). And in Indonesia and Lebanon, nearly six-in-ten would prefer either closer adherence to U.S. policy or maintenance of the status quo (59% Indonesia/55% Lebanon).

A More Democratic Middle East?

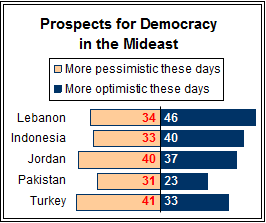

Publics in the predominantly Muslim countries covered by the survey hold mixed views on whether democracy’s prospects are increasing or getting worse in the Middle East.

Pluralities in Lebanon (46%) – and a majority of Christians there (59%) – as well as in Indonesia (40%) say they are increasingly optimistic that the Middle East will become more democratic. Jordanians are divided between those who are becoming more optimistic and pessimistic while the publics in Turkey and Pakistan lean toward pessimism (although 34% of Pakistanis offer no opinion).

Among those expressing growing optimism about Middle East democracy, a 55% majority in Pakistan gives at least partial credit to U.S. policies for their more hopeful view, as do nearly half of both Jordanian and Lebanese optimists. But in Indonesia, despite its generally more favorable attitudes toward America, 63% of optimists give no credit to the U.S. for their higher hopes for Middle East democracy, as did 51% of Turks.

Among those reporting greater pessimism, large majorities (ranging as high as 75% in Lebanon, 83% in Turkey to an astounding 98% in Jordan) lay the blame for their lack of optimism about democracy in the Middle East at least partly on U.S. policies.

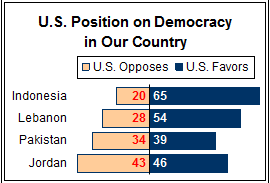

The U.S. is seen as backing democracy in Indonesia and Lebanon by clear majorities of the publics in these countries. But Jordanians and Pakistanis are nearly evenly split over whether America favors or opposes democracy in their nations.

In Indonesia, a solid 65% majority says that the U.S. government favors democracy there. A 54% majority in Lebanon shares this view. But Jordanians and Pakistanis are nearly evenly split, with 46% of Jordanians and 39% of Pakistanis saying the U.S. favors democracy in their country and 43% and 34%, respectively, saying it opposes democracy there (again in Pakistan, a substantial 27% offered no response to the question).

As in past surveys, the poll found most people in predominantly Muslim countries continue to believe that “Western style democracy” could work in their country. This view was most prevalent in Indonesia (77%), Lebanon (83%) and Jordan (80%). Smaller percentages but still pluralities agreed in Turkey (48%) and Pakistan (43%).

Influences on U.S. Policy

When asked to speculate as to which group has the most influence on U.S. policy toward other nations, no clear consensus emerges across countries. Among Americans, 40% say the news media most influences U.S. foreign policy, far more than the number who say business corporations (23%), or ordinary Americans (13%).

In Europe, business corporations generally top the list of influentials, with the news media also mentioned fairly often. The British are most likely to say that corporations have the greatest influence over U.S. foreign policy; roughly four-in-ten (37%) cite corporations as most influential, about twice as many who mentioned the news media (18%).

Despite widespread European perceptions that the U.S. is too religious a country, Christian conservatives are not viewed as wielding much influence over foreign policymaking except in France, where 15% of the public accord primary influence to Christian conservatives, as large a percentage as select the news media. Jews are viewed as most influential by 15% of the public in Poland, 12% in Germany and 10% in Spain.

In both Lebanon and Jordan large majorities say Jews exert the most influence on U.S. policy toward other countries (60% in each). But that view is not shared to nearly the same extent in Indonesia (18%), Turkey (17%), or Pakistan (14%).

Negative Views of War, Iraq’s Future

The sharp drop in America’s global popularity that occurred at the start of the military action in Iraq has not been reversed in most countries, nor have attitudes improved toward the Iraq incursion. Among America’s coalition partners, people in the Netherlands stand alone in saying that their government made the right decision using military force in Iraq. A larger percentage of the Dutch public than the American public says that their country made the right decision to use force in Iraq (59% vs. 54%). The Netherlands dispatched a small contingent of troops to Iraq, which was withdrawn earlier this year.

Among other coalition partners surveyed, however, the judgment is decisively to the contrary. More than two-thirds of the publics in Spain (69%) and Poland (67%) think their countries were wrong to support military action in Iraq. The British public, by a 53% to 39% margin, also believes Prime Minister Tony Blair’s government made the wrong decision to participate in the war.

By the same token, the countries that declined to participate in the Iraq war overwhelmingly reaffirm that decision, with huge majorities in Europe and the Muslim world believing their governments were wise to stay out of the war.

As to whether the removal of Saddam Hussein from power made the world a safer place, views are also lopsidedly negative. In no country surveyed, including the United States, does a majority think the Iraq leader’s overthrow has increased global security. And in Canada and most of Europe – including France, Germany, Spain and the Netherlands – majorities think Hussein’s removal has made the world a more dangerous place. They are joined in this view by majorities in China and all Muslim countries. India is the only country, aside from the U.S., in which a plurality believes the world is a safer place as a result of Saddam’s ouster.

Nor does a majority in any country – again, including the United States – judge that the January elections in Iraq will lead to a more stable situation in that country. In the U.S., optimism about a more stable outcome in Iraq rose from just 29% in January, before the elections, to 47% in February. But those hopes have receded, and now just 35% of Americans expect a consequent gain for stability in Iraq.

In Canada, Indonesia and throughout Europe including Turkey, majorities or pluralities feel that the situation in Iraq will not change much as a result of the election. In Lebanon, a 54% majority predicts that the elections will reduce stability in Iraq. They are joined in this view by pluralities in Jordan, China, India and Pakistan.

Support for Terror War Slipping

The United States finds considerably more support for its leadership in the larger war on terrorism than for the war in Iraq. In the Netherlands, a large 71% majority joins with 76% of Americans in supporting the U.S.-led fight against terrorism. In Poland, 61% of the public also favor the U.S. efforts, joined by small majorities in most other European countries ranging from 55% in Russia, 51% in Great Britain, and France to 50% in Germany. However, in Russia and Great Britain support has declined significantly over the last year.

Canadians, once among the strongest U.S. allies in the war on terror, are now about evenly split on the issue, with 47% opposing the U.S.-led effort and 45% in favor. That represents a significant reversal from May 2003, when two-thirds of Canadians backed the war on terror (68%). Spain has experienced an even more dramatic change of opinion. In 2003, 63% of Spaniards supported the war on terrorism and only 32% opposed it, but now just 26% are in favor while the large majority, 67%, opposes the U.S.-led war against terrorism.

Indonesia is a striking exception to this pattern. The percentage of Indonesians supporting the U.S.-led war on terrorism has more than doubled since 2003 – from 23% to 50%. In most of the Muslim world, however, opposition is widespread. In Turkey, just 17% support the war on terror, down from 37% in March 2004. Similarly in Pakistan support is heavily outweighed by opposition, 22% to 52%. In Jordan opponents of U.S.-led antiterrorism efforts continue to outweigh supporters by a large margin. In Lebanon, views are strongly divided along sectarian lines: Christians support the U.S. anti-terrorism effort by a margin of 60%-33%; Muslims oppose it by an even more lopsided 88%-11%.