Two decades after the end of communist rule, Eastern Europeans have largely embraced democratic values. Most want civil liberties, competitive elections and other tenets of democracy. However, throughout the region there is a significant gap between what people want and what they have, as relatively few believe the elements of democracy that they prize actually characterize their countries.

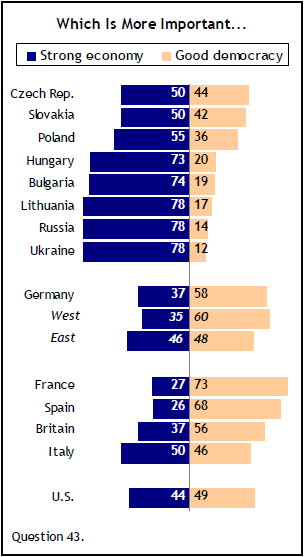

And even though they want democracy, most Eastern Europeans consider a prosperous economy even more important. They are not alone in this sentiment. In these difficult economic times, significant numbers in Western Europe and even the United States also say that if they had to choose between a good democracy and a strong economy, they would take the latter.

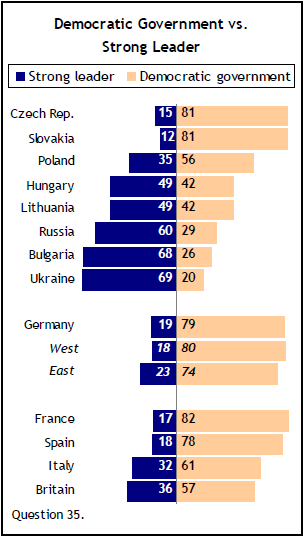

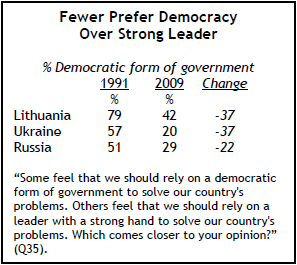

The belief that a strong leader would be better able to solve their countries’ problems than a democratic government is shared by many in Eastern Europe, including majorities or pluralities in the former Soviet republics surveyed: Russia, Ukraine and Lithuania. In each of these three nations, opinions have shifted dramatically since 1991, when in the final days of the Soviet Union, people had far more confidence that democracy would solve society’s ills.

Support for Democratic Institutions and Freedoms

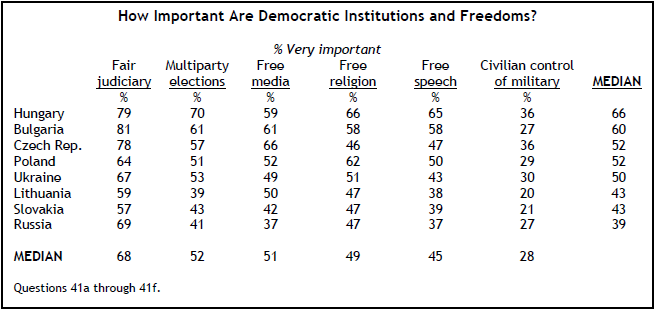

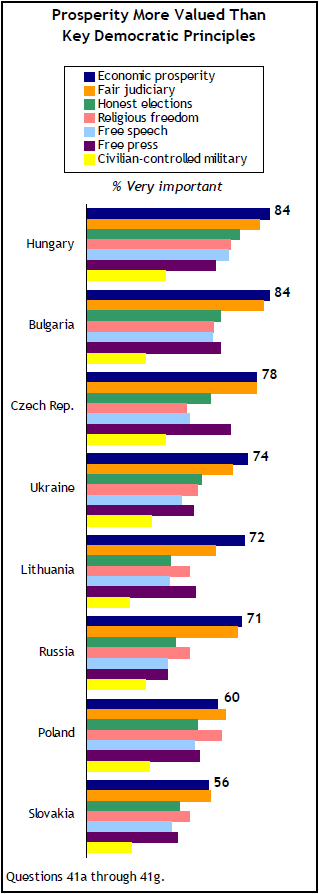

In Eastern Europe, there is widespread support for specific features of democracy, such as a fair judiciary, honest elections, freedom of the press, freedom of religion, free speech and civilian control of the military. In all eight Eastern European nations surveyed, majorities say it is important to live in a country that has these key democratic institutions and values, and large numbers believe it is very important.

In particular, there is consensus about the value of living in a nation with a judicial system that treats everyone in the same way. Majorities in all countries say this is very important; across the eight nations, the median percentage rating this as very important is 68%. Honest multiparty elections are also a priority, although views on this vary somewhat throughout the region. Seven-in-ten Hungarians think it is very important to live in a country with honest elections that are held regularly with a choice of at least two political parties. By contrast, 39% of Lithuanians rate this as very important.

Similarly, opinions about the value of a free press vary. Roughly two-thirds of Czechs (66%) say living in a country where the media can report the news without state censorship is very important, compared with 37% of Russians. Freedom of religion is particularly important to Hungarians (66% very important) and somewhat less critical to Czechs (46%). Hungarians also express the greatest support for free speech: 65% believe it is very important to live in a nation where you can criticize the government and openly say what you think. There is less intense support for this idea in Russia, where 37% say it is very important.

In every country, civilian control of the military is considered less important than the other values tested. A median of 28% in these eight nations say it is very important to live in a country where the military is under the control of civilian leaders. Hungarians and Czechs are especially likely to consider this an important feature of democracy (36% very important in both countries), while Lithuanians are somewhat less likely to hold this view (20%).

Overall, Hungarians stand out for their strong embrace of democratic values. In Hungary, looking across the six values tested, a median of 66% rate these features of democracy as very important. By this measure, Bulgaria is next, with a median of 60%, followed by the Czech Republic (52%), Poland (52%) and Ukraine (50%). Lithuania (43%) and Slovakia (43%) rate somewhat lower, while Russians (39%) are less likely than others to consider these elements of democracy very important.

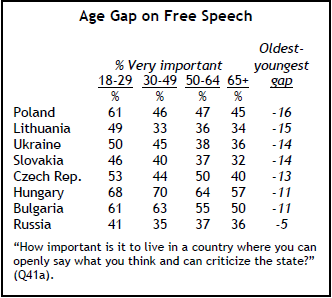

As with many other questions about democracy, younger people, men, those with more education, and urban residents are often especially supportive of democratic values and institutions. One clear example of this is the age gap on the importance of free speech. Younger Eastern Europeans are consistently more likely than their older counterparts to say it is very important to live in a country where you can say what you want and criticize the government.

The Democracy Gap

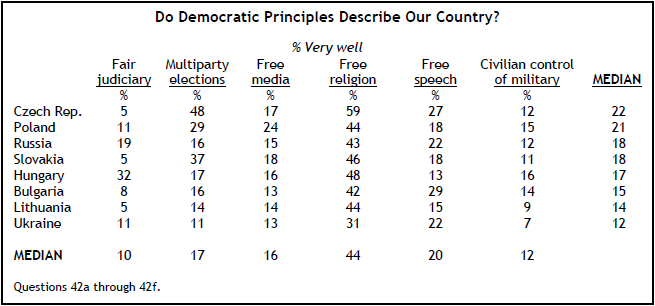

While most Eastern Europeans want democratic values and institutions, many are frustrated by the lack of these elements in their countries. There are substantial differences between support for certain elements of democracy and perceptions of how well countries are doing in ensuring those rights and freedoms.

Of all the democratic principles tested, freedom of religion is the one that Eastern Europeans are most likely to say applies to their country. Roughly six-in-ten Czechs (59%) say the phrase “you can practice your religion freely” describes their country very well, as do more than 40% in every other nation except Ukraine, where 31% hold this view.

For all of the other elements of democracy tested, fewer than half in each country say these things describe their country very well. The feature of democracy most prized by Eastern Europeans – a fair judicial system – is also the one they are least likely to believe characterizes their country. Only 5% of Slovaks, Czechs and Lithuanians think the phrase “there is a judicial system that treats everyone in the same way” describes their country very well.

Overall, Czechs and Poles give their countries somewhat better ratings. Across the six different elements of democracy tested, a median of 22% in the Czech Republic and 21% in Poland say these things describe their countries very well. At the other end, the medians from Bulgaria, Lithuania, and Ukraine are 15%, 14% and 12% respectively.

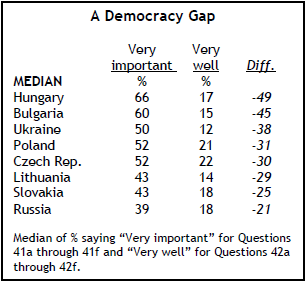

Taking the median percentage saying these values are very important in each country and comparing it with the median percentage saying these values describe their country very well gives us an overall democracy gap for each country. The gap is considerable throughout Eastern Europe, but is largest in two countries where views about national conditions and evaluations of the current state of democracy are especially poor: Hungary and Bulgaria. The gap is somewhat smaller in Slovakia and Russia.

More Want Economic Prosperity

While publics in the former Eastern bloc embrace the key principles of democracy, they value economic prosperity even more. In each country, more rate economic prosperity as a very important objective for their country than say the same about freedom of speech, freedom of the press, honest elections and a civilian-controlled military. And, with the exception of Poland, publics throughout the region are also more likely to say that it is very important for them to live in a prosperous country than it is to live in a country where they can practice their religion freely.

More than eight-in-ten Hungarians and Bulgarians say economic prosperity is very important (84% each), and more than seven-in-ten in the Czech Republic (78%), Ukraine (74%), Lithuania (72%) and Russia (71%) share that view. Smaller majorities in Poland (60%) and Slovakia (56%) rate prosperity as very important.

Few, however, believe they have prosperity. Only 5% of Hungarians say the phrase “there is economic prosperity” describes their country very or somewhat well. Just 13% of Lithuanians and 17% of Bulgarians hold this view. Russians are more likely than any other public to say that there is at least some economic prosperity in their country; 44% describe their country as very or somewhat prosperous, while 51% say Russia is not prosperous.

Democracy vs. a Strong Economy

In another sign of the significance most attach to prosperity, when asked which is most important, a good democracy or a strong economy, respondents in Eastern Europe lean toward the latter. In Ukraine (78%), Russia (78%), Lithuania (78%), Bulgaria (74%) and Hungary (73%), more than seven-in-ten say that if they had to choose, they would prefer a strong economy.

Poles (55%), Slovaks (50%) and Czechs (50%) are somewhat less likely than others to choose a strong economy, although in each of these countries at least half of those surveyed take this view. In the Czech Republic, the preference for a strong economy has become more common since 2002, when 38% held this opinion. Public opinion has moved in the opposite direction, however, in Poland, where 67% preferred a strong economy in 2002, compared with 55% today.

Overall, Germans favor a good democracy (58%), although there is a notable difference between east and west. Six-in-ten west Germans prefer a good democracy, but east Germans are divided on this question (48% good democracy, 46% strong economy).

Americans are also closely divided on this issue, with 49% choosing a good democracy and 44% a strong economy. This is a significant change from 2002, when 61% preferred a good democracy and just 33% said a strong economy.

Democracy vs. Strong Leader

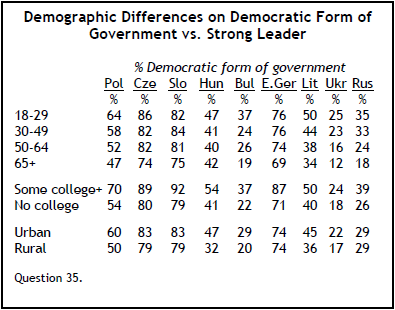

In Eastern Europe, views are mixed on the question of whether a democratic form of government or a strong leader is better able to solve a country’s problems. Roughly eight-in-ten Czechs (81%) and Slovaks (81%) endorse a democratic government, as do a smaller majority in Poland (56%).

Elsewhere, however, people tend to believe relying on a strong leader is the better approach. Slightly more than two-thirds of those in Ukraine (69%) and Bulgaria (68%) say a strong leader is better. Six-in-ten Russians agree, as do about half of Hungarians (49%) and Lithuanians (49%).

In Lithuania, Ukraine and Russia, this question was also included in the 1991 survey. In all three nations, confidence in democracy has waned since that time. The share of the public saying a democratic government can solve the country’s problems has fallen 37 percentage points in both Lithuania and Ukraine, and it has declined by 22 points in Russia.

Since 2002, there has been significant change on this question in both Poland and Bulgaria, although the two countries have moved in different directions. Seven years ago, 41% in both countries said democratic government was the best approach to their country’s problems – since then, this number has increased by 15 percentage points in Poland, while dropping by 15 points in Bulgaria.

Young people, those who have attended college, and urban dwellers tend to express more confidence in democratic government. Poland clearly illustrates this pattern: 64% of 18- to 29- year-olds choose a democratic government over a strong leader, compared with just 47% of those 65 and older; 70% of those with at least some college prefer a democratic government, compared with 54% of those with less education; and 60% of urban Poles select a democratic government, while only 50% of rural residents hold this view.

Individualism

Attitudes toward one of the key values often associated with democracy – individualism – are largely similar in Eastern and Western Europe. In both regions, public opinion on balance leans toward the position that success in life is decided by forces beyond an individual’s control.

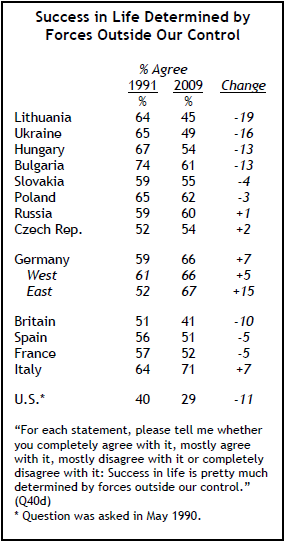

In 12 of the 14 countries surveyed, majorities or pluralities agree that “success in life is pretty much determined by forces outside our control.” That includes solid majorities in former Eastern bloc nations, such as Poland (62%) and Bulgaria (61%), and Western European countries such as Italy (71%) and Germany (66%).

Large shifts have taken place in several former communist countries. The share saying “agree” in Lithuania has dropped by 19 percentage points since 1991, while large declines also have taken place in Ukraine (16 points), Bulgaria (13 points) and Hungary (13 points).

Residents of the former East Germany have moved in the other direction, becoming less individualistic over time. In 1991, 52% agreed that success in life is driven by outside forces; now, 67% hold this view.

The two English-speaking nations are the exceptions on this question. Only 41% in Britain think success is outside a person’s control, down from 51% in 1991.

Individualism is a value often associated with American exceptionalism, and true to form, the U.S. stands apart from the other nations surveyed – only 29% accept the view that success is controlled by outside forces, a drop of 11 percentage points from the early 1990s when four-inten held this view.

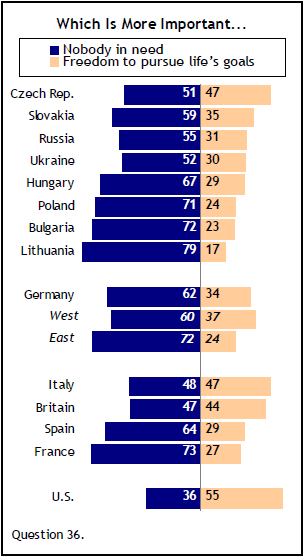

The transatlantic gap on individualism can also be seen on the issue of an individual’s relationship to the state. When asked which is more important, “that everyone be free to pursue their life’s goals without interference from the state” or “that the state play an active role in society so as to guarantee that nobody is in need,” just over half of Americans (55%) consider being free from state interference a higher priority.

In all other countries surveyed, majorities or pluralities say it is more important that the state ensure that no one is in need. Still, there are notable differences among Europeans. Just under half in Italy and Britain say guaranteeing no one is in need is more important, while in Lithuania, France, Bulgaria, east Germany and Poland, more than seven-in-ten take this position.

People in the three former Soviet republics now consider freedom from state interference much less of a priority than they did in 1991. In Ukraine, the percentage saying this is more important dropped by 24 points; similar declines occurred in Lithuania (23 points) and Russia (22 points).