by James Bell, Director of International Survey Research, Pew Research Center

The speed at which pro-democracy movements have redefined the political landscape in countries such as Tunisia and Egypt is impressive. It harkens back to an equally dramatic wave of democratization that took place two decades ago with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet empire and its satellites. While the parallels between former Soviet bloc countries and Middle Eastern nations should not be overdrawn, the experience of Eastern Europe is a useful reminder that public enthusiasm for democracy is not guaranteed as political change extends over years and decades.

The Democratic Moment

When the Times Mirror Center (the predecessor to the Pew Research Center) conducted its first “Pulse of Europe” survey in the spring of 1991, Eastern European publics were widely enthusiastic about democracy. Across the region, sizable majorities approved of the change to a multiparty system of government. Two-thirds or more in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Lithuania, Bulgaria and Ukraine backed the end of one-party rule. In Poland and Russia slightly smaller majorities shared this view.

Eastern Europeans looked forward to a day when democracy would make governments more accountable to the people. As of 1991, only a third or fewer believed that most elected officials cared about the opinion of people like themselves. Confidence that voting would make a difference was also far from universal. Only in the Czech Republic, Bulgaria and Lithuania did majorities feel that voting gave them a say in how government ran things.

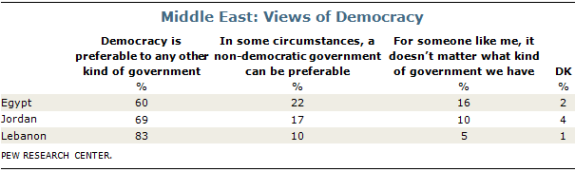

Today, Egyptians and others in the Middle East appear to embrace the view that democracy can rescue the voice of the people and deliver government accountability. In a spring 2010 survey by the Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project, 60% or more among Egyptians, Jordanians and Lebanese said democracy was preferable to other forms of government.

Three years earlier, large majorities in these countries said it was important to live in a country characterized by competitive elections, an impartial judiciary, uncensored media and the freedom to openly criticize the government.

Now that Mubarak has resigned, activists continue to rally in the Egyptian capital. Some appear dedicated to keeping up public pressure so that political reforms are actually put in place. Whether the broader public shares this level of commitment to political change remains to be seen.

The Long Road to Political Reform

For many East Europeans, the fall of the Berlin Wall and collapse of the Soviet Union also ushered in a time of promise and hope. In subsequent years, however, euphoria over democratization gave way to more circumspect opinions about political reform. In part this reflected the difficult, and destabilizing, adjustments imposed by the shift to market economies as well as multiparty systems.

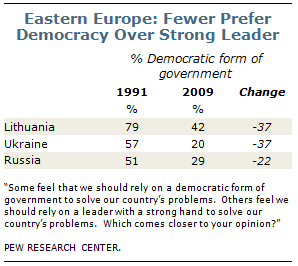

In 1991, majorities of Russians and Ukrainians clearly favored democracy, rather than a strong leader, as the best way to address their country’s problems. By 2002 opinion had reversed, with two-thirds or more in each country saying they preferred a strong leader. In Poland and Bulgaria views were mixed on the issue, while publics in the Czech Republic and Slovakia continued to strongly support democracy.

Seven years on, doubts about democracy persisted. The fall 2009 Global Attitudes survey found Russians and Ukrainians still believing that a strong leader was the best means of solving their country’s problems. Bulgarians now shared this view. In most countries half or more approved of the shift to a multi-party system. But the level of support declined between 1991 and 2009 in all but Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia. In Ukraine, a majority actually disapproved of the change to multiple parties.

These findings do not mean that East Europeans were inclined to abandon democracy. Publics across the region broadly endorsed the demise of communism. Rather these opinions point to the gap between what East Europeans hoped for and what they perceived in terms of political change. On one hand, East Europeans generally agreed that two decades of political and economic change had disproportionately benefited business owners and politicians, rather than ordinary people. On the other, many East Europeans felt democratization had yet to match expectations. In 2009, the median percentage in each country who said a fair judiciary, multiparty elections, uncensored media, freedom of religion, freedom of speech and civilian control of the military were very important significantly exceeded the median percentage who claimed these institutions described their country very well.

That many East Europeans today still see an unfinished political transition suggests that the sprint toward democracy in Egypt, Tunisia and elsewhere in the Middle East is the first leg of a much longer endurance test. Activists and new leaders in countries such as Egypt will inevitably face the challenge of managing public expectations when it comes to the pace and extent of political reform. The experience of Eastern Europe indicates that even when the idea of democracy is broadly embraced, public enthusiasm for political change can be difficult to sustain.