Overview

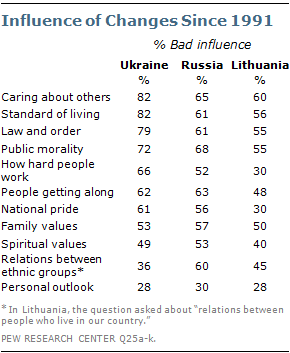

Two decades after the Soviet Union’s collapse, Russians, Ukrainians, and Lithuanians are unhappy with the direction of their countries and disillusioned with the state of their politics. Enthusiasm for democracy and capitalism has waned considerably over the past 20 years, and most believe the changes that have taken place since 1991 have had a negative impact on public morality, law and order, and standards of living.

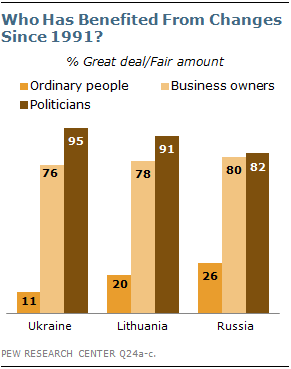

There is a widespread perception that political and business elites have enjoyed the spoils of the last two decades, while average citizens have been left behind. Still, people in these three former Soviet republics have not turned their backs on democratic values; indeed, they embrace key features of democracy, such as a fair judiciary and free media. However, they do not believe their countries have fully developed these institutions.

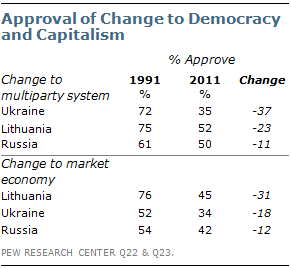

In contrast to today’s grim mood, optimism was relatively high in the spring of 1991, when the Times Mirror Center surveyed Russia, Ukraine and Lithuania. At that time all three were still part of the decaying USSR (which formally dissolved on December 25, 1991).1 Then, solid majorities in all three republics approved of moving to a multiparty democracy. Now, just 35% of Ukrainians and only about half in Russia and Lithuania approve of the switch to a multiparty system.

As was the case two decades ago, the shift towards democracy tends to be more popular among those who are perhaps best positioned to take advantage of the opportunities provided by an open society. In all three countries, young people, the well-educated and urban dwellers express the most support for their country’s move to a multiparty system.

People in these former Soviet republics are much less confident that democracy can solve their country’s problems than they were in 1991. When asked whether they should rely on a democratic form of government or a leader with a strong hand to solve their national problems, only about three-in-ten Russians and Ukrainians choose democracy, down significantly from 1991. Roughly half (52%) say this in Lithuania, a 27-percentage-point decline from the level recorded two decades ago.

When asked about the current state of democracy in their country, big majorities in all three former republics say they are dissatisfied. Moreover, in Lithuania and Ukraine, dissatisfaction has increased in just the last two years. A fall 2009 Pew Global Attitudes survey found that 60% of Lithuanians said they were dissatisfied with the way democracy was working; today 72% say so. In Ukraine, unhappiness with the state of democracy has risen from 70% to 81%.

These are among the major findings from a survey by the Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project, conducted in Russia, Ukraine and Lithuania from March 21 to April 7 as part of a broader 23-nation poll in spring 2011. The survey reexamines a number of issues first explored in a spring 1991 survey conducted by the Times Mirror Center, the predecessor of the Pew Research Center for the People & the Press. This report also presents a number of key findings from a fall 2009 Pew Global Attitudes survey, conducted in these three nations, as well as in 10 other European countries and the United States. (See “ End of Communism Cheered but Now with More Reservations ,” released November 2, 2009.)

Changes Have Helped Elites

Large majorities in all three nations believe that elites have prospered over the last two decades, while average citizens have not. In Ukraine, for instance, 95% think politicians have benefited a great deal or a fair amount from the changes since 1991, and 76% say this about business owners. However, just 11% believe ordinary people have benefited.

The fall 2009 survey further highlighted the extent to which these publics are disillusioned with their political leadership. Few believed politicians listened to them or that politicians governed with the interests of the people in mind.

Just 26% of Russians, 23% of Ukrainians, and 15% of Lithuanians agreed with the statement “most elected officials care what people like me think.” And only 37% in Russia, 23% in Lithuania, and 20% in Ukraine agreed that “generally, the state is run for the benefit of all the people.”

A Democracy Gap

As the findings of the 2009 survey make clear, there is a considerable gap between the democratic aspirations of Eastern Europeans and their perceptions of how democracy actually works in the former Eastern bloc.

In all three former Soviet republics surveyed, the 2009 poll found widespread support for specific features of democracy, such as a fair judiciary, honest elections, freedom of the press, freedom of religion, free speech and civilian control of the military.

Majorities consistently said it was important to live in a country that had these key democratic institutions and values, and large numbers believed most of these features were very important. However, considerably fewer thought their countries actually had these democratic institutions and freedoms.

Less Confidence in Free Markets

Just as views about democracy have soured over the past two decades, so have attitudes toward capitalism. In 1991, 76% of Lithuanians approved of switching to a market economy; now, only 45% approve. Among Ukrainians, approval fell from 52% in 1991 to 34% today. Meanwhile, 42% of Russians currently endorse the free market approach, a 12-percentage-point drop since 1991, eight points of which occurred in just the last two years. In all three nations, young people and the college educated are more likely to embrace free markets.

Waning confidence in capitalism may be tied at least in part to frustration with the current economic situation. Only 29% of Russians say their economy is in good shape, while Lithuanians and Ukrainians offer even bleaker assessments. Among the 23 nations from regions around the world included in the spring 2011 Pew Global Attitudes survey, Lithuanians (9% good) and Ukrainians (6%) give their economies the lowest ratings. (For more, see “ China Seen Overtaking U.S. as Global Superpower ,” released July 13, 2011.)

Moreover, optimism about the economic future is in short supply. More than four-in-ten Ukrainians (44%) expect their economy to worsen over the next 12 months, while 36% believe it will stay about the same, and just 15% think it will improve. Optimism is also sparse in Lithuania, with 31% saying things will worsen, 43% saying things will stay the same, and 21% suggesting the situation will improve. Russians see things a bit more positively: 18% worsen, 46% remain the same, 28% improve.

Negative Impacts on Society

Many in these three nations believe the enormous transformations that have taken place since the demise of the Soviet Union have had negative consequences for their societies. In particular, majorities in all three say the changes since 1991 have had a bad influence on the standard of living, the way people in society treat one another, law and order, and public morality.

Overall, Lithuanians are less negative than Ukrainians and Russians about the impact of the post-Soviet era. For example, majorities in the latter two nations say the changes have negatively affected national pride, while only 30% of Lithuanians hold this view.

Even so, Lithuanians are generally more negative about the impact of these changes today than they were in 1991, when the Times Mirror Center survey asked about the dramatic shifts that were underway. Conversely, Russians and Ukrainians have actually become slightly less negative since 1991, when they were even more likely than they are today to believe the changes were having a bad impact on their societies.

Lithuanian Individualism

Lithuanians also stand apart when it comes to questions about individualism and the locus of responsibility for success in life. Most Lithuanians (55%) believe that people who get ahead these days do so because they have more ability and ambition, compared with only 38% of Russians and 32% of Ukrainians.

Similarly, 58% in Lithuania think that most people who do not succeed in life fail because of their own individual shortcomings, rather than because of society’s failures. Just 47% of Russians and 40% of Ukrainians express this opinion.

Still, there is consensus across all three nations that the state’s role in guaranteeing individual freedom should not trump its responsibility for providing a social safety net. When asked which is more important, “that everyone be free to pursue their life’s goals without interference from the state” or “that the state play an active role in society so as to guarantee that nobody is in need,” more than two-thirds choose the latter in Russia, Ukraine, and Lithuania. Moreover, the belief that the state must ensure that no one is in need has become significantly more common since 1991 in all three nations.

Russian Nationalism

Twenty years after the collapse of the Soviet empire, roughly half of Russians (48%) believe it is natural for their country to have an empire, while just 33% disagree with this idea. By contrast, in 1991, during the final months of the USSR, significantly fewer (37%) thought it was natural for Russia to have an empire, while 43% disagreed.

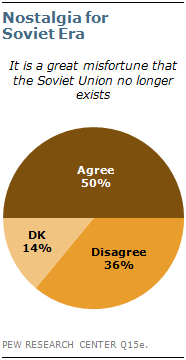

Half of Russians also agree with the statement “it is a great misfortune that the Soviet Union no longer exists;” 36% disagree. This is a slight decline from 2009, when 58% agreed and 38% disagreed. Russians ages 50 and older tend to express more nostalgia for the Soviet era than do those under 50.

Despite widespread nationalist sentiments, Russian attitudes toward Ukrainians and Lithuanians in their country are largely positive – 80% express a favorable view of the Ukrainians and 62% give a positive rating to Lithuanians.

For their part, Ukrainians express overwhelmingly positive views about Russians, Poles, and Lithuanians in their country. Similarly, in Lithuania, attitudes toward Russians, Ukrainians, and Poles are all generally positive.

Looking West or East?

Attitudes toward the European Union and NATO are overwhelming positive in Lithuania, which joined both organizations in 2004. In fact, Lithuanians give the EU its highest rating among the 23 countries included in the spring 2011 poll. Even so, just about half of Lithuanians view their country’s EU membership positively – 49% believe it is a good thing, 31% say it is neither good nor bad, and 8% say it is bad.

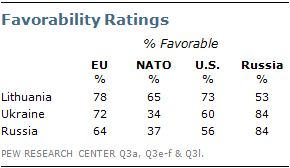

Lithuanians give the United States largely positive marks – 73% have a favorable opinion of the U.S. Attitudes toward Russia are also positive on balance (53% favorable, 42% unfavorable), but not as positive as for the EU, NATO, and U.S.

Most Ukrainians express favorable opinions of the EU (72%) and U.S. (60%), but NATO is not viewed as warmly (34%). The vast majority of Ukrainians (84%) have a positive view of Russia.

As is the case in Ukraine, most Russians give the EU (64%) and U.S. (56%) positive reviews, but not NATO (37%).

Also of Note

- When asked which is more important, a good democracy or a strong economy, more than seven-in-ten Russians, Ukrainians and Lithuanians say a strong economy.

- In Ukraine, a 46%-plurality believes it is natural for Russia to have an empire.

- The belief that ability and ambition determine success in life is consistently more common among young people in these three former Soviet republics.

- Attitudes toward NATO vary significantly by region in Ukraine. About six-in-ten (59%) have a positive view of NATO in the Western region of the country. However, those in the Central (38%), South (21%) and East (18%) regions are much less likely to express a favorable opinion of the security alliance.