A year ago, voters in the United Kingdom narrowly approved beginning a process of leaving the European Union. Today, publics across the European continent think the UK exit will be detrimental for both the EU and the UK. For their part, Britons agree that their country’s exit will be bad for the European project but are divided on what it means for the UK.

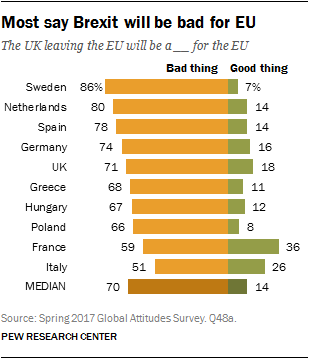

A median of 70% in the 10 EU nations surveyed think Brexit will be a bad thing for the EU. This includes 86% of Swedes, 80% of the Dutch and 74% of Germans. Notably, 36% of the French and 26% of Italians say the UK leaving will be good for the Union. Young people in France, the Netherlands and the UK are more worried about Brexit’s consequences for the EU than their elders. And those on the left in Germany, the Netherlands and the UK are more concerned than those on the right.

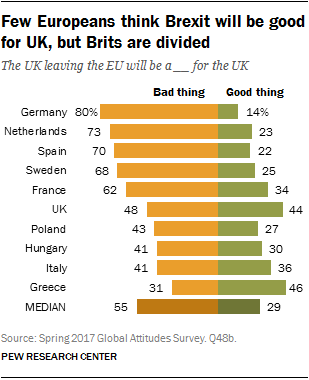

A median of 55% also say Brexit will prove bad for the UK, with Western Europeans more pessimistic than those in Central and Southern Europe. Germans (80%), Dutch (73%) and Spanish (70%) strongly believe that Brexit bodes ill for the UK. A plurality of Greeks (46%) and more than a third of Italians (36%) say leaving the EU will turn out to be good for the British. Notably, about one-in-five Hungarians and a quarter of Poles voice no opinion on the implications for the UK.

The British, for their part, are divided: 44% believe it will be good for the UK to get out of the EU; 48% worry it will be a bad thing.

In many European countries, those on the left are more likely than those on the right to believe Brexit will be bad for the UK. In no country is the ideological divide wider than in the UK itself, where 82% of those on the left say Brexit will turn out badly for the UK and 58% of those on the right say it will be a good thing.

Views of the UK

The British decision to leave the EU may have soured some continental Europeans on their fellow departing member. Favorable views of the UK have fallen 22 points in Spain, 18 points in Germany, 11 points in France and 8 points in Poland since a question on views of the UK was last asked in 2012. Nevertheless, majorities in seven of the nine continental EU nations surveyed still hold a positive opinion of the UK, led by Sweden (78%), Poland (75%) and Hungary (73%).

Sentiment about their departing fellow EU member differs by age in many EU states. Young people, who have no memory of the UK not being part of the Union, are more likely to see the country favorably than older generations, who may have experienced London’s initial rejection of membership in the European Community in 1957 and its subsequent, somewhat reluctant joining in 1973. This generation gap is quite large in France, Germany, the Netherlands and Spain.

Few Europeans want their own exit from the EU

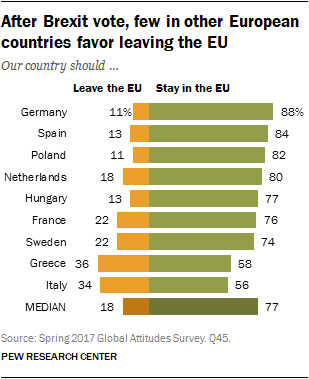

Large majorities across many EU member states surveyed want their nation to stay in the EU.

Eight-in-ten or more in Germany (88%), Spain (84%), Poland (82%) and the Netherlands (80%) back remaining in the EU. More than seven-in-ten in Hungary (77%), France (76%) and Sweden (74%) agree. Even in Greece, where the public is highly critical of the EU, 58% of the public wants to continue to be a member.

A favorable view of Euroskeptic parties does not necessarily translate into support for leaving the EU. In Germany, 69% of those with a positive view of the AfD still want Germany to remain in the EU. In France, 54% of those who voice a positive opinion about the National Front nevertheless back staying in the EU.

Only in Greece and Italy do as many as a third of the public voice support for leaving the EU. In Italy, at least, the prospect of exiting the European project is a deeply ideological issue. Support by those on the right (56%) for leaving the EU is more than twice that found than among people on the left (22%).

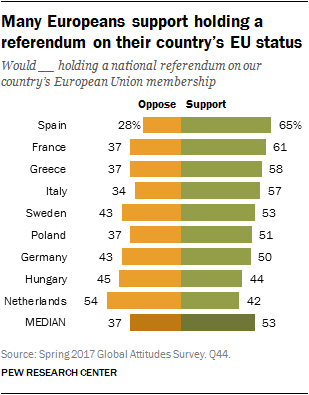

While European publics generally favor remaining in the EU, most also support holding their own national referendum on EU membership, possibly reflecting a broader interest in their voices being heard on such major national issues. Majorities in Spain (65%), France (61%), Greece (58%) and Italy (57%) support such a national vote. And roughly half of Swedes (53%), Poles (51%) and Germans (50%) agree. Hungarians are divided on whether to hold a referendum, while more than half of the Dutch are against it (54% oppose).

The right more than the left backs an EU vote in France, Germany and Italy. But it’s the left more than the right in Spain that wants such a vote, including 80% of those who favor Podemos. Not surprisingly, given their Euroskepticism, 84% of those who favor the National Front in France want a referendum on continued EU membership. In Germany, 69% of those who favor the AfD also want their own vote, as do 69% of those who favor the PVV in the Netherlands and 63% of those who favor the Five Star Movement in Italy.

On immigration and trade: Less Europe

Support for remaining in the EU is strong across continental Europe. But so is support for taking back some powers from Brussels.

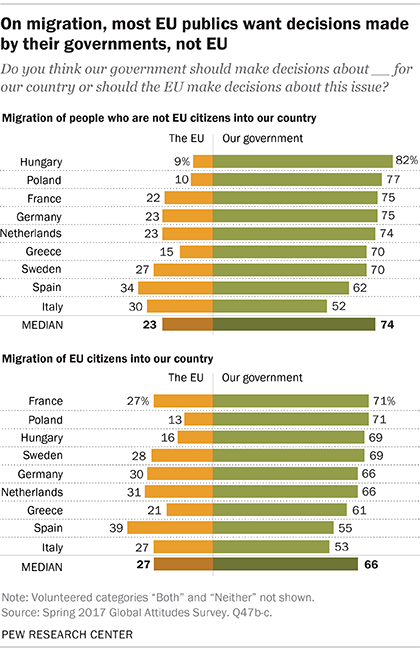

A total of 2.4 million migrants settled in the 28 EU countries from non-EU member nations in 2015. Many were refugees from war-torn Syria and North Africa. European publics are quite critical of the EU’s handling of refugee issues. And they want their national governments to be the ones making decisions about the migration of non-EU citizens into their countries.

Roughly eight-in-ten in Hungary (82%) and seven-in-ten or more in Poland (77%), France (75%), Germany (75%), the Netherlands (74%), Greece (70%) and Sweden (70%) want their national government to make such judgements, not Brussels. In France, Hungary, Italy, Poland, the Netherlands and Sweden, it is people on the right more than people on the left who back national sovereignty over external immigration. In Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden, people ages 50 and older are more likely than those 18 to 29 to want their national government to control such immigration. But in Spain, it is younger people who are more likely to want Madrid to control such policy.

The free movement of people within the EU is one of the core four freedoms – along with the free movement of capital, goods and services – guaranteed by EU treaties. And in 2015, 1.4 million people migrated from one EU state to another. But in 2017, more than half in all nine EU nations surveyed want their own governments to make the rules about the migration of EU citizens into their countries. Roughly seven-in-ten in France (71%), Poland (71%), Hungary (69%) and Sweden (69%) want their own capitals, not Brussels, to make such decisions. Italy and Poland join France, Hungary, the Netherlands and Sweden as societies where the ideological right is more supportive than the left of the exercise of national sovereignty over internal migration. Germany and Sweden are again the countries where there is a generational gap on views of such movements of people, with older respondents more likely to say power should reside with national governments.

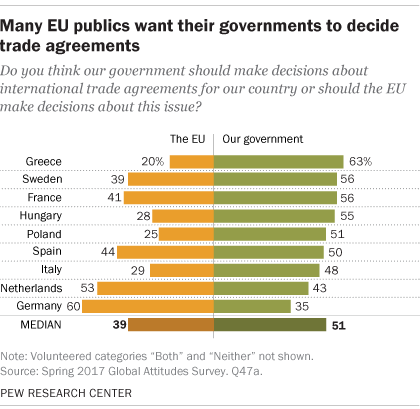

The authority to make trade agreements has rested with Brussels since 1957, when the European Economic Community, predecessor of the EU, was created. In recent years such accords have been met with a great deal of public resistance. And majorities in Greece (63%), Sweden and France (both 56%), and Hungary (55%) want the power to make trade deals back in the hands of their national governments, as do about half of Poles, Spanish and Italians. Only Germans (60%) want trade agreement authority to remain with the EU. In France, Hungary, Italy and the Netherlands, more people on the right than on the left want to reclaim trade decision making. And it is older people more than younger people in France, Germany and the Netherlands who want to reclaim that sovereignty.