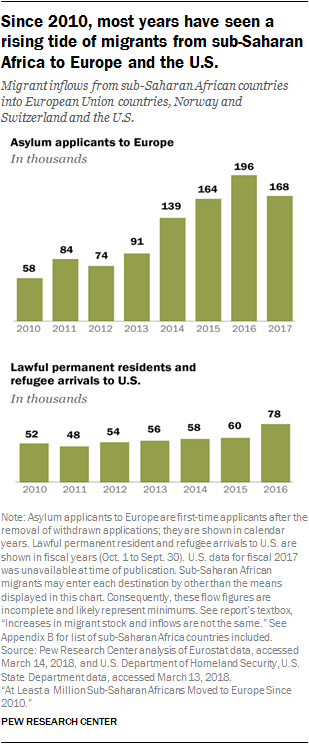

International migration from countries in sub-Saharan Africa has grown dramatically over the past decade,1 including to Europe2 and the United States. Indeed, most years since 2010 have witnessed a rising inflow of sub-Saharan asylum applicants in Europe, and lawful permanent residents and refugees in the U.S.

The factors pushing people to leave sub-Saharan Africa – and the paths they take to arrive at their destinations – vary from country to country and individual to individual. In the case of Europe, the population of sub-Saharan migrants has been boosted by the influx of nearly 1 million asylum applicants (970,000) between 2010 and 2017, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of data from Eurostat, Europe’s statistical agency. Sub-Saharan Africans also moved to European Union countries, Norway and Switzerland as international students and resettled refugees, through family reunification and by other means.3

In the U.S., those fleeing conflict also make up a portion of the more than 400,000 sub-Saharan migrants who moved to the States between 2010 and 2016. According to data from U.S. Department of Homeland Security and U.S. State Department, 110,000 individuals from sub-Saharan countries were resettled as refugees over this seven-year period. An additional 190,000 were granted lawful permanent residence by virtue of family ties; nearly 110,000 more entered the U.S. through the diversity visa program.4

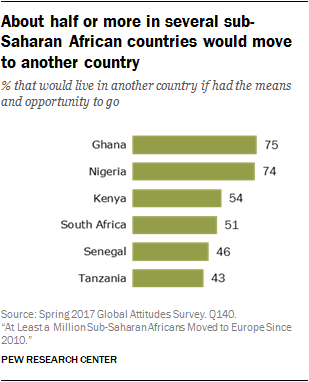

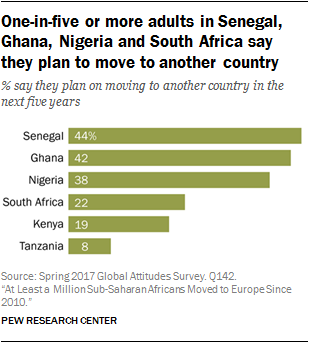

Will the inflow of migrants from sub-Saharan Africa to Europe and the U.S. continue at the same pace in the years ahead? It is difficult to say. However, the idea of migrating is on the minds of many Africans living south of the Sahara. According to a 2017 Pew Research Center survey in six sub-Saharan countries that have supplied many of the region’s migrants to the U.S. and Europe, many say they would move to another country if the means and opportunity presented themselves. And in Senegal, Ghana and Nigeria, more than a third say they actually plan to migrate in the next five years. Of those who plan to move, more individuals plan to move to the U.S. than to Europe in most countries surveyed.

Increases in migrant stocks and inflows are not the same

About 420,000 more sub-Saharan African migrants lived in Europe in 2017 (4.15 million) than in 2010 (3.73 million). And an estimated 1.55 million sub-Saharan African migrants lived in the U.S in 2017, an increase of about a 325,000 from 2010, when an estimated 1.22 million sub-Saharan African migrants lived in the country, according to the United Nations. These populations are also sometimes referred to as migrant stocks. They constitute the balance of increases and decreases in the total accumulated population of sub-Saharan migrants for a specified time period.

Inflows, by contrast, in this report refer to the annual migration of people born in sub-Saharan Africa to Europe and the United States. Inflows can boost the total migrant stock if inflows to a region or country exceed the combined effects of deaths, outflows and return migration to countries of origin. As a result, in some instances, differences in migrant stocks between two time points can be lower than inflows.

EU countries, Norway and Switzerland received nearly 1 million first-time asylum applications from sub-Saharan Africans between 2010 and 2017, according to data from Eurostat, Europe’s statistical agency. (This number removes application counts withdrawn by sub-Saharan Africans between 2010 and 2017 to account for the possible duplication of asylum seekers applying in multiple countries). But asylum applications are not the only way sub-Saharan migrants enter Europe. Some enter, for example, on family or work visas, or as resettled refugees or international students, so the total inflow is likely larger.

At the same time, U.S. Department of Homeland Security and U.S. State Department records indicate that more than 400,000 sub-Saharan Africans entered the U.S. between fiscal 2010 and fiscal 2016 as arriving lawful permanent residents or resettled refugees. (Data from fiscal 2017 were unavailable). A smaller number of sub-Saharan Africans also entered the U.S. as international students or as employees with work visas.

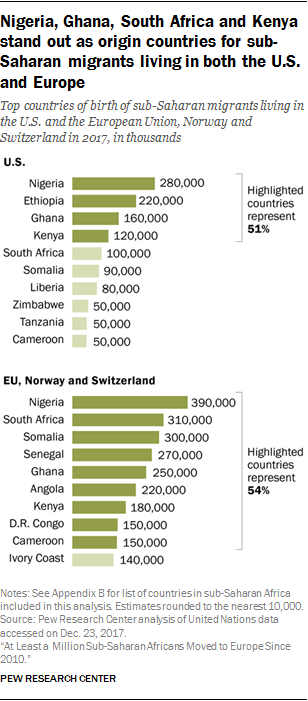

Nigeria and Ghana have been major sources of sub-Saharan migrants to both Europe and the United States

More than half (51%) of sub-Saharan African migrants living in the U.S. as of 2017 were born in just four countries: Nigeria, Ethiopia, Ghana and Kenya, according to migrant population data from the United Nations.5

Nigeria, Ghana and Kenya are also major sources of migrants to the EU, Norway and Switzerland. However, compared with the U.S., sub-Saharan migrants to Europe arrive from a more diverse set of origins, with more than half of migrants living in Europe born in South Africa, Somalia, Senegal, Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Cameroon, in addition to Nigeria, Ghana and Kenya.

Some origin countries of these sub-Saharan migrant populations in the U.S. and Europe have increased more than others. For example, between 2010 and 2017, the total number of Somalian migrants in Europe increased by 80,000 people. Over the same period, the total population of Eritreans living in Europe climbed by about 40,000, according to UN estimates.

In the U.S., between 2010 and 2017, several sub-Saharan migrant populations increased, including those from Nigeria (70,000 individuals), Ethiopia (70,000) and Ghana (40,000).

In terms of destinations, as of 2017, nearly three-quarters (72%) of Europe’s sub-Saharan immigrant population was concentrated in just four countries: the UK (1.27 million), France (980,000), Italy (370,000) and Portugal (360,000). In the U.S., migrants from sub-Saharan Africa can be found across the country, with 42% in the American South, 24% in the Northeast, 18% in the Midwest and 17% in the West.6

If circumstances permitted, many sub-Saharan Africans would migrate abroad

Between February and April 2017, Pew Research Center surveyed in six of the 10 countries that have supplied many of the sub-Saharan immigrants now living in the U.S. Four of these countries – Nigeria, Senegal, Ghana and Kenya – are also among the top 10 origin countries for sub-Saharan migrants to Europe.

The survey asked respondents whether they would go to live in another country, if they had the means and opportunity. At least four-in-ten in each sub-Saharan country surveyed answered yes, including roughly three-quarters of those surveyed in Ghana (75%) and Nigeria (74%).

The relatively high shares of people in these countries who say they would resettle in another country is generally consistent with findings from other surveys, like Afrobarometer in Nigeria and Ghana, that pose questions about the desirability of migrating. Compared with other world regions, Gallup polls find that sub-Saharan countries have some of the highest shares of people who say they would move to another country.

What’s behind the widespread appeal of migrating in some sub-Saharan countries? Multiple factors could be at play. To begin with, while many sub-Saharan African economies are growing, many countries continue to have high unemployment rates and relatively low wage rates. In addition, the job market looks unlikely to improve anytime soon, thanks to high fertility levels that will mean even more people competing for jobs. Against this backdrop, sub-Saharan Africans could see migrating to countries with more – and better paying – jobs as a means of improving their personal economic prospects.

Political instability and conflict are other factors pushing sub-Saharan Africans to move. For example, the number of sub-Saharans displaced within their own country nearly doubled to 9 million between 2010 and 2016, according to United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates. Also, the total number of refugees from sub-Saharan countries living in other sub-Saharan countries grew about 2.3 million in the same period. At the same time, reports indicate that anywhere between 400,000 and a million sub-Saharan Africans are in Libya; some of them have been sold as slaves or are being held in jail-like facilities.

Pressures related to economic well-being and insecurity may help to explain why, beyond a general willingness to migrate, substantial shares of sub-Saharan Africans say they actually plan to move to another country in the next five years. Among the six countries polled, the share with plans to migrate ranges from roughly four-in-ten or more in Senegal (44%), Ghana (42%) and Nigeria (38%) to fewer than one-in-ten in Tanzania (8%).

Will all those with plans to migrate in fact leave their home countries in the next five years? If recent history is a guide, the answer would most likely be no. But data from official sources suggest that this will not be for lack of effort.

For example, 1.7 million Ghanaians (or 6% of Ghana’s population) applied for the U.S. diversity lottery in 2015, even when only 50,000 people worldwide are permitted to move each year to the U.S. through this visa program. In the same year, other sub-Saharan African countries, such as the Republic of Congo (10%), Liberia (8%) and Sierra Leone (8%) saw high shares of their populations apply for the lottery. Although the lottery only requires an online application and the completion of a high school diploma for eligibility, the high number of applicants underscores the seriousness with which many sub-Saharan Africans contemplate and actively pursue migrating abroad.

In some sub-Saharan countries, U.S. preferred over Europe as destination

Europe’s border statistics show a well-traveled route of migrants from Africa to Europe. But this does not necessarily mean Europe is the top choice of potential sub-Saharan African migrants. In fact, in several of the countries surveyed by Pew Research Center, those planning to migrate more often cited the U.S., as opposed to Europe, as their preferred destination when asked where in the world they planned to move.

For example, among the 42% of Ghanaians who say they plan to migrate abroad in the next five years, four-in-ten (41%) identify the U.S. as their intended destination, while three-in-ten (30%) name a country in the EU, Norway or Switzerland. Similarly, shares of potential migrants in South Africa (39% vs. 22%) and Kenya (39% vs. 12%) say they intend to migrate to the U.S. over Europe.7

Only in Senegal, a Francophone country, do more respondents that plan to move intend to migrate to a European country (49%), as opposed to the United States (24%).

The survey did not ask respondents why they preferred the U.S. or Europe, but it did ask whether respondents were in personal contact with friends or relatives in other countries. People planning to migrate in the next five years tended to identify destinations where they already had friends or family. This finding is generally consistent with studies showing that personal connections influence the decision and likelihood of migrating.

Higher shares of adults in Senegal and South Africa say they have friends or relatives they stay in touch with regularly in Europe than say this about friends or relatives in the U.S. Meanwhile, in Ghana, Nigeria and Tanzania, people have friends or relatives they stay in touch with in Europe and the U.S. at about the same rate. In Kenya, a higher share of people have contacts in the United States.

Sub-Saharan Africa includes all countries and territories in continental Africa except Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, Sudan, Tunisia and Western Sahara. Sub-Saharan Africa also includes the islands of Cape Verde, Comoros, Madagascar, Mauritius, Mayotte, Reunion, Sao Tome and Principe, Seychelles, and St. Helena. For a complete list, see Appendix B.

Migrants includes people moving across international borders for any reason, including economic or educational pursuits, family unification, or flight from conflict, which can apply to refugees and asylum seekers.

Europe is used in this report as a shorthand for the 28 nation-states that form the European Union (EU), as well as Norway and Switzerland, for a total of 30 countries. At the time of this report’s production, the UK was still part of the European Union, even though the country triggered Article 50 on March 29, 2017, to begin its withdrawal from the EU.

The terms asylum seekers, and asylum applicants are used interchangeably throughout this report and refer to individuals who have applied for asylum in a European country after reaching Europe. All family members, whether male or female, children or adults, file individual applications for asylum. Reported figures in this report are first-time asylum applicants with counts of withdrawn applications removed. See “Still in Limbo: About a Million Asylum Seekers Await Word on Whether They Can Call Europe Home” for more information on Europe’s asylum seeker process.

U.S. lawful permanent residents (previously known as legal permanent residents) or green card holders are granted permanent residence in the U.S. based on a complex system of admission categories and numerical quotas. Most are immigrants sponsored by family members, either as immediate relatives of U.S. citizens or other family members of citizens and lawful permanent residents.

Refugees denotes the group of people fleeing conflict to a nearby country. Resettled refugees are refugees (often living in a neighboring country), who are processed and approved for resettlement. They later move to countries like the United States or those in Europe.